By Kevin Koopman, 1st year UBC medical student (Class of 2017)

The Dominican Republic (DR) and Haiti are two dramatically different nations sharing one island, each with their own culture, government, currency, and language. Sadly, Dominicans have developed a deep-rooted racial prejudice towards Haitians, resulting in on-going exploitation of Haitians on sugar cane plantations. In 1821, Haiti invaded the Dominican Republic and ruled it for 22 years. The effects of this historical conflict are demonstrated by the Dominican Republic’s ruling class, who continues to assert that everything that has gone wrong with their country is solely the Haitians’ fault – this “bad blood” may ultimately explain the government’s limited response to the detrimental problems in the bateys (company towns where sugar plantation workers live).

Before the sugar cane plantations shut down 15 years ago, the DR Government would illegally transport Haitians across the border to the Dominican Republic during the night and employ them for the “dirty work” on the plantations. There was one important caveat to this arrangement: workers would have their Haitian citizenship removed, making them neither Haitian nor Dominican Republic citizens. The workers were brought to the bateys where they were crammed into small shacks, and their undocumented state rendered them unable to leave. Once inside the bateys, residents were essentially immune from the Dominican immigration authorities, who neither checked on immigration status nor threatened the residents with deportation. Attempted escape resulted in one of two possibilities: the batey resident would be shot by Dominican police, or would be deported back to Haiti. If returned to Haiti, they would no longer be considered a Haitian citizen and would subsequently be thrown into jail.

Today, the bateys are small sugar cane communities composed of left over scrap materials found in nearby dumpsters. The population shares small rooms that often lack basic hygiene. In most bateys, there are no sewage systems, electricity, running water, trash collection, or paved streets. The children play in ditches filled with muddy, parasite-ridden water and wander around garbage heaps with rats, flies, and mosquitoes. These conditions contribute to life-threatening diseases, in an environment where there are virtually no medical dispensaries available for treatment. Life expectancy in these areas is very low compared to the general population of the Dominican Republic. Teenage prostitution is the only “work’ available for young women and this often results in the delivery of a newborn in a less than sterile environment.

Infectious diseases are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population of these bateys. Despite immunizations resulting in the eradication of many infectious diseases in developed countries, routine pediatric immunizations have remained unattainable in the Dominican Republic. Most children living in the bateys are not immunized against common childhood illnesses like Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus, Mumps, Measles or Rubella, and even if they were, no records are kept, making clinical evaluations nearly impossible.

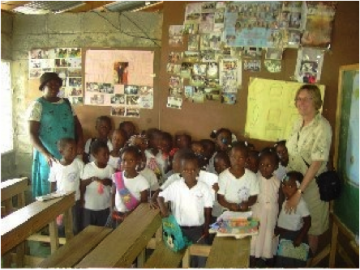

Despite the Dominican Republic displaying the beginnings of a social welfare society, free medical coverage and partially subsidized education are only available to DR citizens. In 2004, the Dominican government passed an immigration law denying citizenship to the children of Haitian immigrants. Thus, Haitian children born on the bateys have no documentation of citizenship and are not entitled to medical services or an education. Project École Ébenezer was started to promote the educational rights of Haitian children living in Munoz, Dominican Republic. We currently help to provide these children with a fundamental education (textbooks, supplies, and uniforms included), nutritional and dental assistance, and essential medical care.

In March 2013, my wife and I ventured down to volunteer at École Ébenezer for 3 months. Our accommodation was cheap, rustic living and truly in the middle of nowhere. Our walks to the Haitian village occurred on Dominican side roads where we engaged in smiles with local Dominicans followed by a mispronounced “hola.” The presence of locals carrying machetes was nerve wracking at first, but a simple smile and nod of acknowledgement defused the tension after a couple weeks. The kilometer walk to the village presented its challenges at times; taxis passing each other on the wrong side while speeding (a simple honk meant, “move because I’m not stopping”), clogged roads from herds of cattle being led by their machete-yielding masters, piles of road kill left to rot for days, wagered cock fights (wives were a usual bet) attracting large crowds, and my personal favorite – quirky remarks toward my wife asking if she needs a boyfriend. The presence of Caucasians roaming the Dominican streets was nothing new since our accommodation attracts numerous adventurous humanitarians each year, but a cautious skepticism (“are you sure this was a good idea?”) crept into our minds more than once. This was our life for 3 months but we loved every minute of it.

Our experience at the school was like no other. We taught English twice per week to whomever wanted to attend, played sports with the children, held weekly lunches, coordinated arts and crafts days, brought children back to our place for supervised swims, and had spirited dance-offs. For someone looking for a structured volunteer experience, this would not be for you! Our English classes were the same day and time each week but Haitian time dictated an entirely different schedule: 1:00 pm classes would start at 2:00 pm because children and adults simply “forgot,” arts and crafts time meant “mayhem management time” because all the children wanted in on the action, dividing up the kids to play soccer quickly transformed into every man for themselves, while spirited dance-offs led to children running wild. For my wife and I, this was the perfect concoction of what we were looking for – a non-structured experience where we could truly feel involved with the local culture. Some days we would arrive at the village to just hang out and cuddle the children. We quickly learned that the simplest and often most effective thing we could bring to the village was love. Children of all ages were longing for a physical connection and embracing love, likely because the culture emphasizes the value of independence, beginning as early as the child is old enough to walk.

Before I close, I want to reiterate some important points. Firstly, we did not bring down money to simply give to the locals. We empowered them to work hard by making bracelets, handmade peanut butter, and ornaments from which they could generate income, and thus strengthen the local economy. If you carry someone for too long, eventually they will forget how to walk. That was our mentality going into the trip. The organization does not have a “money solves all” mentality – if you have volunteered abroad, you will certainly be aware of the damaging effects of this approach. Secondly, linguistics experts might notice that Ébenezer roughly translates into “God with us.” While very true, having a religious affiliation is not necessary if one wants to volunteer. While a majority of the men are pastors and the church is beside the school, all religious or non-religious beliefs are welcomed with open arms by the Haitians. Lastly, while illegally returning to Haiti is an option for these Haitians, life in Haiti is worse for them even than in the Dominican. While it is arguable that both the Haitian children and the school should be in Haiti, the stark reality does not make this possible. Needless to say, the situation has consolidated into a convoluted political mess, therefore establishing École Ébenezer in the Dominican Republic was the only option.

If you are at all interested in venturing to École Ébenezer I would be more than happy to discuss everything from flights, accommodation, food, transportation, and establishing connections with Haitian friends to help you with your trip. Unlike other volunteering programs, volunteering at École Ébenerzer is simple: buy your plane ticket (Vancouver, BC to Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic for $700-900 return-trip), book your accommodation (~$200 per month with a discount the longer you stay), and figure out what you want to do. Teach music, play sports, teach art, or simply just hang out with the children as many days as you like. The beach is 5 minutes away so you can go to the beach every day. There is no weekly minimum volunteer requirement or minimum duration of stay; you are the director of your trip so be creative – anything goes!

I can be contacted at kkoopman@alumni.ubc.ca for further discussion on volunteering or just global health in general. Visit École Ébenezer on Facebook for pictures of the projects we have completed (roads, buildings, playground, benches) and the loving children who stole our hearts.